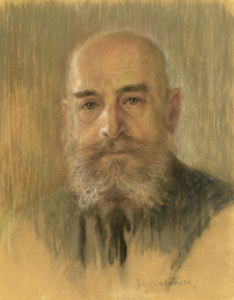

Orest Dournovo was a genuine humanitarian who organized hundreds of Russian refugees to find freedom and farming in Canada in the 1920’s. Sadly, there are no posthumous awards either provincially or federally to recognize his past deeds. At best, his past work can be explained here in this tribute to him.

Early days of Dournovo saw him raised in an aristocratic Russian family with land and fortune. His parents favoured that his formative years be spent in a military academy to produce a good soldier. Dournovo was more interested in the prestige of the uniform in society than the pursuit of warcraft. To that end, he often used his position in society to garner work that focused on the care and treatment of his fellow soldiers. In time he became a force in building military hospitals for the Imperial army. Dournovo was also a devout Christian who practiced his Orthodox faith with his family.

Dournovo sensed change was happening to his country’s political landscape. He decided to move his family further eastward to avoid the turmoil and restlessness of the big cities, but he soon found that the troubles would follow them wherever they journeyed in Russia.

The Dounovo family ended up in Harbin, China, the eastern outpost for Russian expatriates. His family struggled without having any financial resources. However, the one asset that remained with Dournovo was his uncanny ability of connecting with people at, or above, his station. This is how he connected with the following players: Prince Alexander Golitzin, Commissioner, Russian Red Cross, Mr. W. J. Egan Deputy Minister of Immigration for the Canadian Government, and his assistant Mr. F. J. Blair, Mr. J.S. Dennis, Chief Commissioner of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), Department of Colonization and Development, Mr. R. P. MacGrath, Executive Secretary, Russian Refugee Relief Society of America Inc. (RRRSA).

Golitzin was registering and categorizing some 16,000 Russian refugees in Harbin as skilled or unskilled as part of his work with the Red Cross. Canada had recently been asked to take in 1,000 Russian refugees by the League of Nations to help stem the Russian refugee crisis. Egan also had an ulterior motive to develop the Canadian Prairies farmland with immigrant farmers. Dennis’ CPR was the transportation conduit to Canada, and they supplied the colony when the settlers arrived in Canada. He worked closely with Egan to plan refugee movements. Lastly, MacGrath represented an organization that provided financial support Russian expatriates landing in North America.

It is unclear how Dournovo connected with Golitzin, perhaps it was in the local sober (Orthodox church) where Dournovo often supplied the priests with liturgies (he had also published a book in Western Russia before the revolution entitled, “So Spoke Christ”), but in May 1924 Golitzin presented Dournovo as the organizer of the first group to head to Canada.

Dournovo prepared a list of 30 families for vetting by Canadian authorities. They wanted skilled farmers, but a cursory view of the list had all sorts of backgrounds. Dournovo’s daughter would say, “But father did not go into details, the principle was first come, first served, and our family”.

Time was an enemy to many involved in this process. Lists had to be sent for approvals halfway around the world and visas had to be issued after approvals were received back in Harbin, China. While waiting for clearances, refugees could not work and thus savings needed to be drawn for everyday living. Therefore, it should not be surprising when the official word came to travel, only twenty of the thirty families had the money needed to go. A Pacific transit fare on the CPR ships cost $57 per passenger in the day and the Canadian Government wanted each family to carry $400 disposable income. Dournovo, working without any compensation for his efforts thus far, was among the ten families unable to go. The Old Believers in the group quickly assessed their situation and agreed that one way or another, they needed to have the chief organizer travel with them. Funds were raised and the Dournovo family travelled with the first 116 Russian refugees to Canada.

Much was made of the required Landing Money set as a condition of entry into Canada by W. J. Egan. Fortunately for the refugees, Dournovo had the RRRSA fulfil the Government’s requirement of $25,000 for the first group. This set an unfamiliar tone for other refugees coming from Europe who faced no such requirement. Unknown to Dournovo was Egan’s bias toward the Russians and Chinese as “non-preferred” immigrants. In retrospect, this explained a lot of the delays and foot dragging on the part of the governmental officials in visa approvals.

After successfully landing in the CPR colony farm of Homeglen, Alberta, the refugees set about organizing their next four-year commitment to the colony life. Mr. Dennis reported to Egan the refugees were thriving and asking to have the next group come forward. It would not be until the spring of 1925 that the next group would be approved. A poor harvest was cited as the reason to hold the refugees back.

In the fall of 1924, the Government asked the colony to build a meeting hall and plans were supplied to guide them. As the leader of the group, Dournovo decided he would pay workers a good wage for their work using the landing money resources for this purpose. This would prove to be Dournovo’s undoing. Those who chose not to work on the project thought Dournovo was unfair in using the money in this manner. Their sour grapes complaints would ultimately lead to Dournovo’s removal from the colony.

Dournovo and his family were moved to Calgary where through 1925 and 1926, where he continued working with his contacts in Harbin. Their method was to prepare a list of families showing their composition, ages and amount of landing money. Once this list was vetted by immigration officials, the families were permitted to obtain visas from the British Consulate in Harbin. Over the two years 18 such lists were prepared by Dournovo with more than 1,000 family names.

The Government was not comfortable with this method. They questioned who this “organization” was? Was it a Society? Did it have any legal status? Some people on the lists came, while others had to stay behind. Then when those that had stayed were now ready to come, another list was presented. This makeshift movement of people led to a change in the Government’s procedure. The refugees in Harbin were now required to obtain a letter of approval from the Government. They would then take that forward to obtain their visa to enter Canada. This effectively ended Dournovo’s organization and its movement of refugees to Canada. In 1928 the Government ultimately changed its passport requirements and all immigration from China was stopped.

Dournovo’s job of bringing his fellow countrymen to freedom and farming faced constant friction from the Government. Delayed approvals, financial commitment not required of others immigrants, English as a second language for prompt communications, and supply of sufficient farm land made Dounovo’s job more difficult. Through out his work he represented his organization in a professional manner as reflected in his numerous correspondence to both Egan and Blair.

It should be noted the move to Calgary left Dounovos family impoverished. His daughters had to work outside the family for subsistence. Dournovo had performed all his humanitarian work of bringing refugees to Canada without any compensation from the Government. When asked if Dournovo’s efforts should be recognized by the Government, Blair writes in a May 4, 1926 memo, “Mr. Egan stated that the Department could not possibly make a grant for Col. Dournovo’s support in view of the precedent that would thereby be established.”

On the other hand, Dournovo’s daughter explains, “A letter from the CPR. They said that summing up in connection with immigration they came to the conclusion that father had achieved for them was more than their best agents had done selling their lands [this was the Government of Canada’s stated objective]. And they were happy to resompence (sp) him with a final thousand dollars … at the time it was not too bad.”

Dournovo wasn’t just finding freedom for refugees, he was likely saving lives considering the turmoil in both China and Russia at the time. A similar individual in the second world war who made lists and saved some 1,200 people was Oskar Schindler. They wrote books and made a movie about him. Orest Dournovo had the same heroic qualities only several decades earlier.

He was but one man who selflessly organized lists of Russian families. One man who obtained their approvals and permissions to enter Canada. One man who found them farmland to raise their families. He was one man who created peace and freedom for hundreds of refugees and thousands of future generations. Orest Dournovo was, A Real Canadian Hero.

P.S. It would be fitting for a family member or a friend to pay a tribute to Orest at the planned Centennial Anniversary celebrations planned for next June 2024 in Homeglen, Alberta.

Public Archives – Chronological sort

Dournovo’s Lists and Correspondence (likely incomplete)

A grim summation of the many obstacles put in the path of such a large number of Russian refugees attempting to flee from their last haven in China as they fled the Bolshevik forces, and were then being expelled by Chinese government decree. Thanks for highlighting this part of the struggle that evolved.